John Edward Black Military Experience

[This post is published posthumously in the exact draft form that it was found – Joseph, September 29, 2021]

Military Service:y 1948 to 1952

Military Service:y 1948 to 1952

Sergeant First Class Natio

Staff/Sergeant U. S. Armnal Guard 1954 to 1962

Chief Warrant Officer U. S. Army Reserve 1962 to 1970

Basic Training, Fort Ord, California

I joined the army right after World War II ended. I was 17 years. My self and a high school friend, Guy Worthen, signed up under a “Buddy” system whereby, after basic, we would be sent to Sam Houston Army Hospital in Houston, Texas to be trained as Surgical Technicians. We were sent to Fort Ord California for thirteen weeks of infantry training. Upon completion of basic training, Guy was sent to Sam Houston Army Hospital for training. I believe he was eventually sent to Korea and I never heard from him again, nor could I find out what happened to him.

The attached photo was taken in San Francisco on our first of two passes we had during basic training. We were all excited to see the city and when we got off of the bus we were immediately arrested by Military Police, because we had the wrong hats and insignias on. We were detained at the MP station until late at night when they took us to the bus station and put us on the last bus to Salinas, just a few miles from Ft Ord. We did get one more pass, which we used to wander around Salinas for the day.

Ordnance School, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland

At the end of basic training I was informed that my tests indicated I would make a better mechanic than a Surgical Technician. Consequently, I was sent to the Ordnance school at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, Maryland to be trained as a Tank mechanic.

APG, as they called it, occupies a land area of 293 square miles. Its northernmost point is near the mouth of the Susquehanna River where it enters the Chesapeake Bay.

I spent four months learning how to repair the M24 and M26 tanks. The barracks we lived in were only about a city block from the Chesapeake Bay. For recreation one could check out row boats and tool around in the bay.

Being sent to Aberdeen may very well have been the best thing that could have happened to me. As it turned out, graduates from the tank mechanic school were the only MOS (Military Occupation Specialty) being sent to Europe. All other specialties were either sent to Japan or Korea. Before my enlistment was up, the Korean War broke out and many of my high school friends ended up in combat in Korea, some never to return. I never saw or heard from Guy Worthen, my buddy whom I joined with.

After graduating from tank mechanic school, I got orders to report to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey in preparation for deployment to Germany. Because I was only allowed four days to go from APG to Camp Kilmer, I traveled back to Provo to see my family, not knowing when I would ever get back from Germany. It took all my time to just get home so I went to the American Red Cross and asked for their help in getting an emergency leave. They helped arrange a one week visit with my family. I didn’t think about it at the time, but this delay had a major effect on where I would spend the next years. I got back to Camp Kilmer just in time to spend Christmas 1947 in a cold, unheated barracks. Two days later I found myself in the back of a truck heading for a Port of Embarkation in New York City.

Crossing the Atlantic to Bremerhaven, Germany

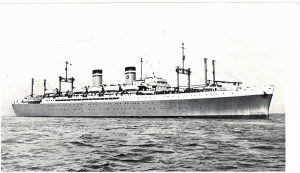

As I walked up the gang plank of the USS Private Murphy, I was sure I would never see the United States again. This was just after the Russians cut off all access to Berlin from the West, which would become known as the Berlin Blockade, or Berlin Airlift. There was a lot of talk about the Russians actions starting a Third World War.

Liberty ships were developed very early in the Second World War to haul freight. Overall, there were over 6,000 ships built and most of them were sunk by German U-Boats and Japanese submarines. There are only two left in existence today (2015). One is docked in San Francisco, California and the other in Baltimore, Maryland.

Because a Liberty ship was built for hauling freight, it had to be modified to haul troops. This was done by taking a frame made of steel pipe and stretching canvas in between. These frame beds were stacked six high around the side of the area where freight would have been at one time. We had the feeling we were sardines in a can. It took a little over two weeks on the ocean before we docked at Bremerhaven, Germany.

Introduction to Germany

We were unloaded from the Private Murphy late in the afternoon and immediately loaded on a train for an overnight trip to Marburg, Germany for processing. Upon arrival at Marburg, we were bused from the train station to the barracks which would be our home for the next week. Once settled in our room, because it was still dark, we all lined up to the windows to see what our first real view of Germany would be. As daylight broke the first thing that caught our attention was a castle that overlooked the barracks where we were assigned to stay.

The next thing was a strange looking car parked across the street. It was a cold morning and a man came out and raised the back hood and low and behold there was a motor under it. The engine was in the trunk! One of the fellows who had been overseas during the war told us it was a Volkswagen.

The personnel Sergeant who was processing me informed me that because I missed my original scheduled date of arrival, the vacancy I was scheduled to fill had been taken. A year later I learned I had been scheduled to be an instructor at the European Ordnance School. After a few days not knowing where I would end up, I was told to pack up my belongs move into an upstairs room, along with eleven other GI’s. In the dead of night we were awakened and loaded on a bus that took us to an airfield in Frankfurt, Germany. We were loaded onto an Air Force DC3. Once airborne, we were told our destination was Berlin, Germany. This was not good news in that it just reinforced my thoughts I would never see the United States and home again.

Welcome to Berlin

We landed at Templehof Airport in the center of Berlin. Templehof was, and still is, one of the largest airport buildings in the world. Templehof airport was one of two airfields in Berlin at the time I arrived, the second being Gatow airfield, located in the British Sector. Tegel, which was located in the French Sector, was under construction. It was constructed over a period of a couple months at the beginning of the airlift to accommodate French planes bringing coal and flour to Berlin. Tegel was built primarily by men and women workers using wheelbarrows because they did not have any heavy construction equipment. The workers would fill their wheelbarrows with gravel and dump them on the landing strip. When an airplane approached, a whistle would blow alerting them so they could get out of the way. Once the aircraft had landed, they would go back to work. The irony is that Templehof and Gatow were closed over the years and Tegel is now one of two airfields currently in operation (2015).

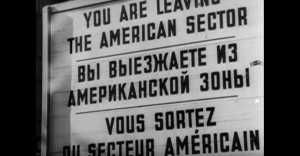

As part of a short orientation, were were informed that we were 125 miles inside the Russian Zone, which was the home of about 100,000 Russian troops. Also, the city was divided into four Sectors, which were governed independently by the United States, Great Britain, France, and Russia. We were warned that we should be aware of where we were at all times. There were signs everywhere you went designating sector and zone boundaries. All signs were in English, Russian, and French. Even the passes we used when we left the barracks were in four languages. You never knew when you would get stopped and asked for your ID. We were told we could move freely between the three Western Sectors, but the Russian Sector and Zone were off limits. Accidently crossing into the Russian Sector was not to bad. The Russian MP’s were usually forgiving, but crossing into the Russian Zone would mean the military would have to negotiate to get you back, which usually took a few weeks.

After the brief orientation we were loaded into the back of a truck driven by a Constabulary Trooper for a seven mile ride to McNair Barracks. Along the way it was overwhelming to see the devastation caused by the massive bombing and shelling that Berlin had undergone. It was a very cold morning and I have a memory of passing areas where women were working, cleaning up the debris of what was once their apartments. They all wore dresses, coats, and shoes. They had rags wrapped around their legs to keep them warm. It was so cold. A sight I will never forget. The following video illustrates exactly what it was like when I arrived upon the scene in Berlin.

McNair Barracks (Telefunken)

I was relieved when I found McNair Barracks, my new home base, was on the edge of Berlin and had not been the target of Allied bombing. It was like being out in the country. McNair Barracks was originally constructed before the Second World War to manufacture radios for the Telefunken company.

I was relieved when I found McNair Barracks, my new home base, was on the edge of Berlin and had not been the target of Allied bombing. It was like being out in the country. McNair Barracks was originally constructed before the Second World War to manufacture radios for the Telefunken company.

Upon arrival, I was assigned to a US Army Ordnance detachment, whose primary responsibility was to maintain all vehicles used to unload the airplanes as they arrived at Templehof airport.

It was a surprise to find out that everyone stationed at McNair got the same meager rations as the German people, which was 1700 calories a day. All coal, flour, food, and supplies had be flown in to Berlin. In addition, there was only electricity one hour a day, from 5 to 6 pm. The only light in the barracks after 6 pm were candles spaced evenly along the window ledges.

Except for two Army schools I attended for periods of a few months, and the year detached duty at the Ammunition depot, McNair barracks would be my home.

The Berlin Airlift

When I arrived in Berlin, the Berlin Blockade, or “Airlift” as air force personnel called it, was in full force. It was a “blockade” for those of us who lived on the ground, and an “airlift” for those who flew back and forth, spending only enough time on the ground in Berlin to unload cargo. The Berlin airlift became known as the largest humanitarian effort ever undertaken. There will never be anything like it again. The airlift lasted a year and during this time all food and supplies necessary to support 2.3 million Germans was supplied and delivered solely by American, French, and British governments and their people.

In addition to the humanitarian aspect, it was a tremendous repatriation effect in that governments and people from all the western countries come together and contributed food and supplies to be flown into Berlin for the local residents, which a few years earlier had been their enemy. It was also amazing that many of the airlift planes were piloted by bomber pilots who, a few years earlier, were dropping bombs on the city. On the other side, many of the Germans who volunteered to unload and distribute food, coal, and flour, had been fighter pilots or soldiers, who had fought against against us just a few years earlier. One pilot who flew bombing missions over Berlin a few years earlier was heard to say, as he looked around while his plane was being unloaded, “These people look just like us”.

My first morning of duty I was called to the First Sergeant’s office for an interview. He informed me, because of the “four power agreement,” there were no tanks in Berlin. Because of my training as a tank mechanic, MOS, he was not sure where to place me. After working in the supply room for about a month, I was told I was going to Darmstadt, Germany to attend the U.S. Quartermaster School for six weeks to learn how to be a supply clerk. Because Berlin was blocked from the outside world by the Russians, it was necessary for me to catch one of the airlift airplanes returning to Frankfurt, Germany. Once there I caught a local train to Darmstadt which was just outside Frankfurt. Upon graduation, I caught a plane at Rhine-Maine airfield loaded with coal heading back to Berlin behind the “Iron Curtain.”

As part of settling in I became friends with another soldier who had served a previous tour overseas and was much more experienced than me. This fellow had a motorcycle and I would ride with him over to the french sector on weeks to get away from the military police. One weekend the 1st Sergeant saw us on the motorcycle and on Monday morning I was called into his office and was told that he was not the type company I should hang around with. To separate us he informed me that, effective immediately, I was being assigned to the Ammunition Depot, which was in the forest next to Lake Wannsee, about 6 miles from McNair barracks.

Berlin Ammunition Depot, Lake Wannsee

As part of my orientation I was informed about the dangers involved in handling the various explosives I would be dealing with. I was also informed that I would be reporting to the Ordnance School in Eschwege, Germany for a six week Ammunition NCO course. So it was back catching a flight out of Berlin on an airlift plane to Frankfurt and train ride to Eschwege. Once there I found out that the east side of the village was also the Russian zone border. I had a wonderful panoramic view of the city from the window of my barracks which was on a steep hill on the west side of town. The barracks were originally built and inhabited by the German army. After spending a couple months in Berlin, a city of 3.5 million people, where you saw devastation everywhere you looked, it was so refreshing to look out the barracks window and see such a beautiful view.

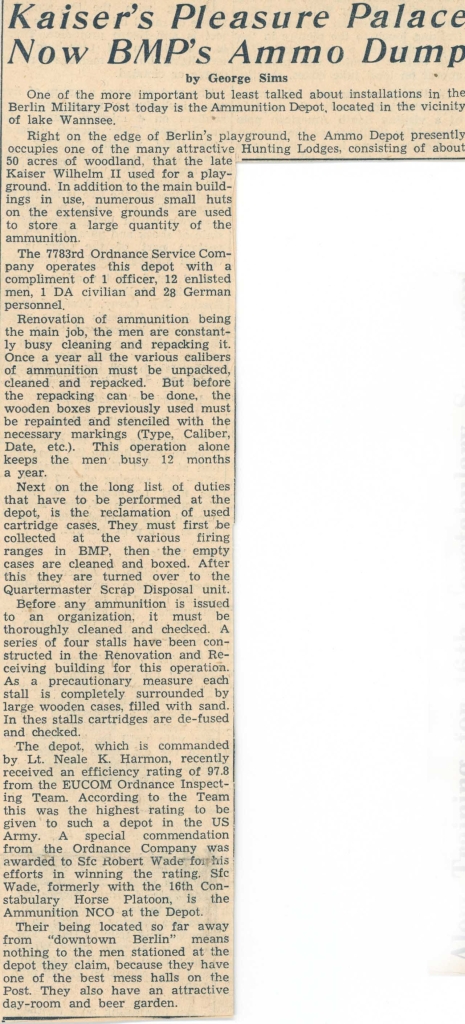

The Ammunition Depot occupied 50 acres of land on the West side of Berlin adjacent to Lake Wannsee. Two sides of the property served as the border between the American Sector of Berlin and the Russian Zone. Russian infantry men, armed with their sub machine guns and driving jeeps that the United States provided them during the last days of the war, patrolled the Russian side, while United States First Infantry soldiers patrolled the other.

An article published in the European edition of “Stars and Stripes,” best explains our activities:

Other duties, not mentioned in the article, were to pick up unexploded bombs and artillery shells as they were found in the rubble of bombed buildings and then defuse and destroy them.

Upon arrival to Lake Wannsee I was pleasantly surprised to find I would live in the hunting lodge built for and used by Wilhelm II, Kaiser (Emperor) of Prussia during World War I.

Life at the hunting lodge was very good. Because we were a critical installation, we had power twenty-four hours a day, and full rations. We had three German women who worked in the lodge. Two of them prepared our meals and the other was a seamstress who took care of our clothes. I shared an upstairs room with another person. In the center of our room was a pot bellied stove, which the Germans made sure we had plenty of wood to burn. When I first got there it was very cold but we were always warm and comfortable.

There was a Belgium citizen who was over all the German workers. His name was Joseph Van de Kelch. He had been an underground fighter during the days the Germans occupied Belgium and it’s hard to say how many Germans he had killed while doing that. Considering what he had gone through when the Germans occupied Belgium, he seemed to be pretty fair with the people he supervised.

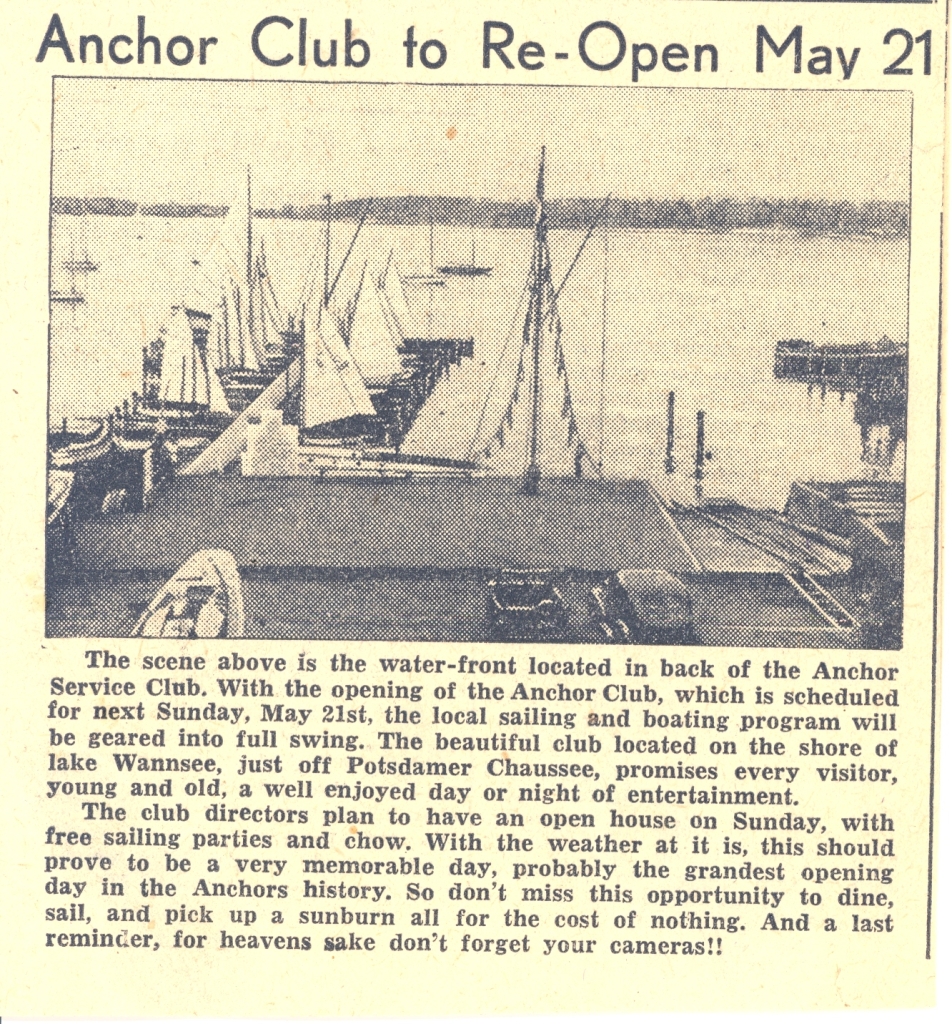

About a quarter of a mile away there was a US Army service club called the “Anchor Club.” This club was not open officially during the airlift. The building and boats were managed by four Army MP’s and about four German civilians. The MP’s had their meals with us in our mess hall. They returned the favor by letting us ride along with them while they patrolled the lake on weekends. The sailboats and kayaks at the club had been used in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The club being closed did not keep us guys from the Ammunition Depot using the equipment any time we wanted. I took sailing lessons from an old German man who taught me all the basics. We spent much of our time sailing and kayaking around the lake.

This opening was in celebration of the official ending of the Berlin Airlift. However, for fear the Russians would have a change of heart, the airlift continued until September.

Berlin Lake Wannsee is really two lakes, Kleiner (small) Wannsee and Grosser (large) Wannsee, which are formed by wide spots in the river Havel. The small Wannsee actually forms the boundary line between Berlin and Potsdam.

At the bottom part of the small Wannsee was bridge named the “Glienicker Brucke.” This bridge was about a half mile away from where I lived and over the years became known as “The Bridge of Spies”. Because it was on the border of the American sector of Berlin and Potsdam in the Russian Zone, it was a convenient place where spies were exchanged between the Americans and the Russians. As a matter of fact, in 2015, Steven Spielberg made a movie entitled “The Bridge of Spies.”

The bottom part of the photo where all the trees are was part of the Kaiser II, Wilhelm Hunting Lodge aka Ammunition Depot. The “Bridge of Spies” is just outside of this photo, in the upper left corner where the water narrows.

I was always curious about the quarters we lived in, given they had been built and occupied by a King of Germany. For some unknown reasons, one day I decided to explore a crawl space up in the rafters. I found an envelope with cancelled stamps and a postcard that had been around the world on a Graf Zeppelin in 1929 during a “good will trip”. It had been postmarked at all major stops that it made. After I got back to the US, I had the postcard appraised and found, because of all the cancellations, it was worth considerable money. I kept it for a rainy day which turned out when my Christine was born. Because we did not have health insurance, I sold the postcard, along with a couple of other stamps, to pay for her hospital expenses.

After a year the Russians relented and opened the ground and water access to Berlin. Late in 1948, when things started to normalize after the Airlift, the Ordnance detachment I belonged to was phased out. We were given a week to find a new home. None of us had any interest in leaving Berlin, but we did take the time to spend a week touring the American Zone of Germany. I got to visit the European Ordnance School and have a reunion with all the fellows I went to tank mechanic school, which was a lot of fun. After the vacation, I applied to join the United States 16th Constabulary and was accepted.

United State Constabulary

The United States Constabulary was designed at the end of World War II as an elite mechanized police force to keep order within the population while possessing significant combat capability.

The United States Constabulary was designed at the end of World War II as an elite mechanized police force to keep order within the population while possessing significant combat capability.

All units were designated as United States Calvary Troop, primarily because many of them had horse mounted troops as part of their organization. All individuals were called “Troopers,” not soldiers. The day to day duties consisted of patrolling the American Sector, maintaining order among the civilian population, looking for anything unusual, and responding to demonstrations and unruly crowds. This type of police force worked well in Berlin because there was considerable unrest, unruly crowds, and riots primarily caused by the East Germans.

The one exception to being mobilized was the Headquarter (HQ) Troop I belonged to. This included one platoon of horse mounted Troopers. The horses were very effective in crowd control in that nobody wanted to be stepped on by a horse. This platoon was the last official horse Calvary Unit in the United States Army.

Before my three year enlistment was up, the Korean War broke out and we were all automatically extended by an additional year. Also, one morning we fell out for morning formation and were informed that, effective immediately; the 16th Constabulary had fulfilled its mission and was deactivated. The term “Calvary” became history. From then on units with armor and helicopters were designated as “Armored Calvary.” On a “go forward basis” we would be designated as the US Army 6th Infantry Regiment. We were informed that within days we would be leaving for Grafenwohr, Germany to receive three month’s infantry training. All constabulary units were deactivated at this time.

6th Infantry Regiment, Berlin, Germany

When the Constabulary was deactivated, I was transferred to Company A, 6th Infantry Regiment to serve as a Supply Sgt. In an Infantry company of 204 soldiers, the best jobs were 1st Sgt, Platoon Sgt, Supply Sgt, and Mess Sgt. A great way to serve out the last couple years of my enlistment.

When the Constabulary was deactivated, I was transferred to Company A, 6th Infantry Regiment to serve as a Supply Sgt. In an Infantry company of 204 soldiers, the best jobs were 1st Sgt, Platoon Sgt, Supply Sgt, and Mess Sgt. A great way to serve out the last couple years of my enlistment.

The role of the infantry was to be a placeholder in a city surrounded by over a hundred thousand Russian troops. In addition to routine infantry duties and training, we were assigned to guard war crime prisoners at Spandau Prison on a rotating basis with French, British, and Russian troops. The seven war criminals that were not hanged at the end of the Nuremberg trials included Admiral Karl Donitz, who replaced Hitler in the last days of the war. Thinking back, it’s hard to comprehend looking through the cell windows and watching these prisoners who held such responsible positions in the Hitler’s Third Reich. To a 19 year old Sergeant it was just another duty assignment.

At the end of my four year enlistment, I was called to personnel and given the choice of spending another three years in Berlin, or going home and being discharged. I chose the latter and the next morning went back to personnel and picked up my travel orders.

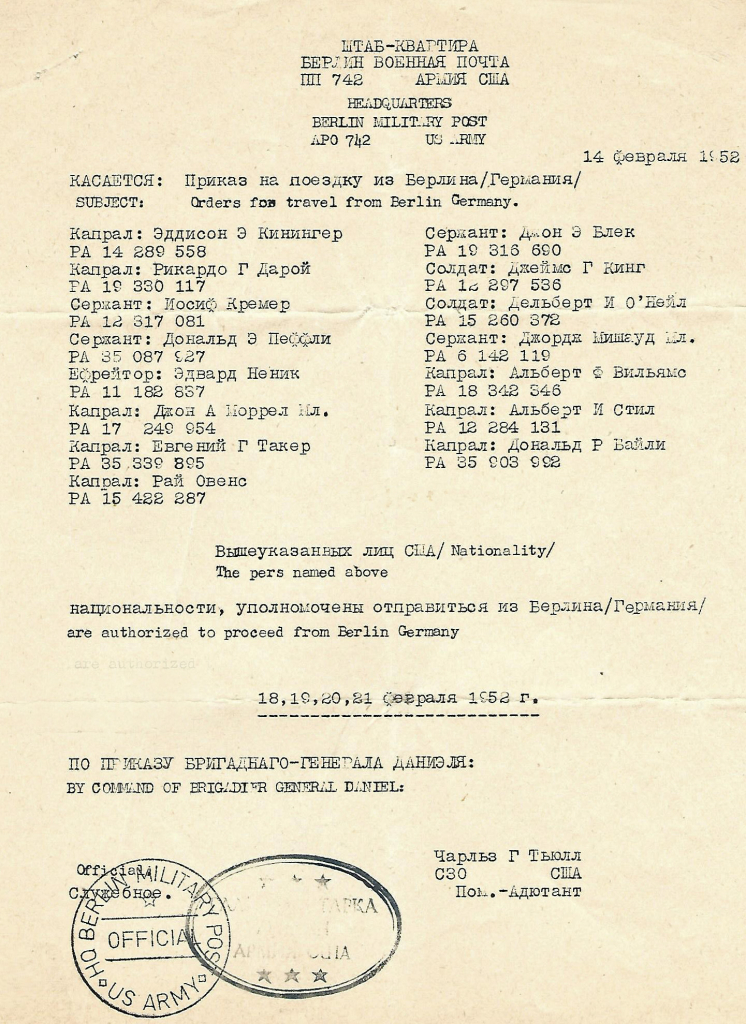

In the evening I reported to the Berlin railway station and boarded the “Berlin Express,” for an overnight trip to Frankfurt, Germany. The Berlin Express had compartments that would sleep two people, and was very comfortable. As the train was leaving the station the conductor came through and notified us that all blinds on the windows must be closed while going throught the Russian Zone, which was 125 Miles. When we arrived at in the city of Potsdam, which was just down the road from the Ammunion Depot, where I had been station earlier, we were boarded by Russian Military Police long enought for them to check everyone’s travel orders. When they were throught they left the train and we went on our way. this was my last experience of the Russians I had. Once we were in Frankfurt, we were transferred to another train that took us to Bremerhaven, Germany, our port of embarkation for the United States.

Ocean Crossing From Bremerhaven Germany to New York City

After processing in Bremerhaven, I boarded the USNS General Maurice Rose and set sail for New York. Unlike the Private Murphy which brought me to Germany, the Rose was a “Twin Stacker,” meaning it had two exhaust stacks. It also had twin screws that propelled us through the water. It was about the size of a year 2000 cruise ship.

Don’t know why, but I was assigned as prison 1st Sergeant over 45 general prisoners being brought back from Germany to the Federal prison in Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. I had one Sergeant reporting to me and we worked out a 12 hours on and 12 hours off schedule. The prisoners were hard-core having been sentenced for long terms for crimes ranging from murder to embezzling money from the government. The brig where these prisoners were kept was at the front and bottom of the ship’s bow, which is the worst place you can imagine being. About three days out, the wind began to blow and by dark it was blowing at 80 mph, or hurricane speed. The motions the ship was going through was indescribable. Although it was not my shift, around midnight I went down where the prisoners were and they were yelling and screaming because they wanted to be let out in case the ship started to sink. The other sergeant had told them “no chance”. I was 20 years old at the time with three year’s military experience. Consequently, I opened up the cell doors and let them come out and sit on the floor. We sat on the floor until the wind subsided and they went back in their cells and I locked them up. They expressed to me how appreciative they were and from that day on they followed my orders to the letter.

End of Nearly Four Year Tour in Germany

In 1952, after nearly four years in Berlin, I returned home to the United States of America. Thinking back, if it had not been for getting the emergency leave right after graduating from Tank Mechanic School, and the offset of time that that created, I would have spent years standing in front of a classroom saying the same thing day after day instructing young GI’s how to maintain an M26 tank. Instead, I had the privilege and opportunity of seeing a lot of history being made.

Post Active Duty

I served in the National Guard ———–

I spent a number summer camps at Gowen Field, Boise, Idaho, as a Supply Sgt. The last summer camps were spent at Camp Irwin, California as a M45 tank commander.

and in the US Army Reserve until 1971, at which time I was retired as a CWO (Chief Warrant Officer).

/-111.9677,38.8405,12/300x200@2x.png?access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoiamJlcmdlbiIsImEiOiJjanRxb3d1NWgwaHBuM3lvMzJ3emtyNWY4In0.xCCZGVjZrBAKn5C_O6q8CA)