Sara, “The Indian Girl,” Harrop

Sarah, “The Indian Girl,” is the Mother of Phoebe Lorraine Harrop Black

Stacy Julin is the great, great, Grandaughter of Sarah. In her poem she makes reference to the blanket that was “paid” for Sarah. The blanket was one of the most important possessions an Indian could have. For an Indian, a blanket was a comforter at night while sleeping, protection against the elements, and to be wrapped in for burial.

Raising Sarah

In the book where Richard Benson kept all these dates he also had the date of September 15, 1853, when he bought a little Indian girl for a blanket which the Indian mother was very glad to get. This little Indian girl, whom the Bensons named Sarah, and their foster daughter, Elizabeth Parker, made ten children for the Bensons. The two babies, Thomas and Joseph, who died in infancy back east, left eight children that Richard and Phoebe reared to adulthood.

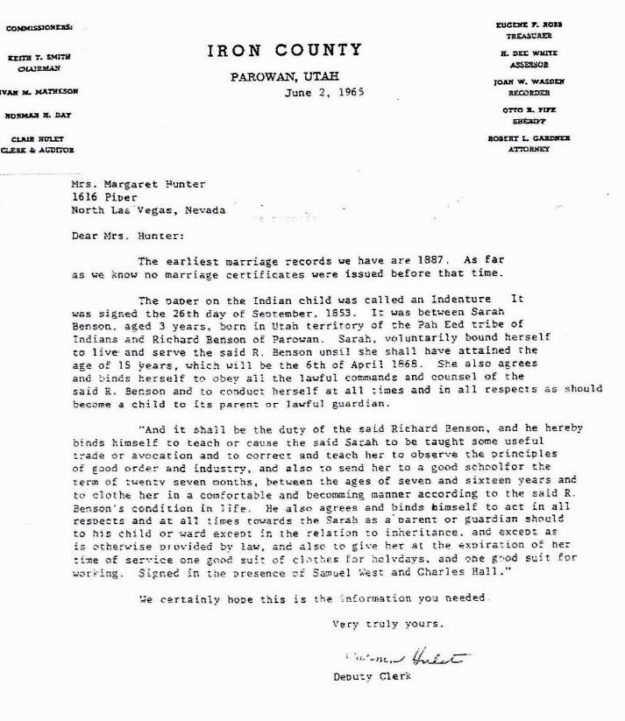

One of the first things Richard Benson did was initiate an Indenture that stated “Sarah voluntarily bound herself to live and serve the said R Benson until she will have attained the of 18.” The purpose of this indenture was to protect the Benson’s against any claim she might make against the Benson family, or their estate.

A blanket made by Phoebe Benson, which illustrates her blanket making skills, is on display in the DUP museum in Parowan, Utah.

When Sister Benson was asked what she did first when she found the little Indian child was now her own, she said she went in and gave it a bath, put clean clothes on it and burned the rags she had on. The family was always very kind to this Indian girl named Sarah. She was taught to mend her clothing and help with the house work. Sister Benson said she could bake bread to perfection. Sarah would watch the-bread every minute of the time it was baking, but she was never allowed to mix the bread or do any other work where she had to use her hands next to the food.

Sarah grew up in the family as one of them and the children were never allowed to mistreat her in any way. Their son, Richard Heber, would say that his mother always made him dance with her at the dances” and when he was young he sure did hate it. She was taught to cook, sew, and scrub floors and all the things that her white brothers and sisters were taught. Her Daughter Phoebe Lorrain said Sarah was built like the Benson’s, tall and thin, whereas the Indians were shorter and heavier. Sarah grew to womanhood and married a frenchman (Englishman) by the name of Henry Harrip (Harrop). To this union were born several children. Sarah loved to ride horses and took good care of her family. She braided their hair, put ribbons in, kept them clean and loved them a great deal.

Sarah and Henry Harrop were devout Latter Day Saints. They went to the St. George Temple and were sealed and had their children sealed to them. The original Benson home, where Sarah was raised, still stands in Parowan, Utah.

Roberta B. Rowley, Grandaughter of the Benson’s, in a 1965 letter to Margret Hunter, talks about compiling a history of the Benson family from journals and first hand information in which she writes: In the book where Richard Benson kept all these dates he also had the date of September 15th 1853 when he bought a little Indian girl for a blanket which the Indian mother was very glad to get. When sister Benson was ask what she did first when she found the little Indian child was now her own, she said she went in and gave it a good bath, put on clean clothes and burned the rags it had on. The family was always very kind to this Indian girl named Sarah. She was taught to mend her clothing and help with the housework. Sister Benson said she could bake bread to perfection. Sarah would watch the bread every minute of the time it was baking, but she was never allowed to mix it (because of her brown hands.) Sarah grew up in the family as one of them and the children were taught to treat her same as they did the other members of the familyI have heard the oldest boy Richard Heber say his mother always seen to it that he danced with Sarah as well as his other sisters. I have heard my mother say that the Indian girl was not the child of the Indian woman who sold her but was a child that had been stolen from another tribe. The Bensons were always friendly to the Indians who come to their home asking for food. My mother said that Grandma Benson told her that she had a brightly pieced quilt on a bed when this Indian woman came in and it caught her eye so she begged grandma to give to her in exchange for the baby. I have no way of knowing the age of the child but I have been told she was only about two year of age as much as they could tell. From a letter written to Richard Benson, when he was on his second mission to England, by his wife Phoebe. This letter is post marked December 24, 1866 I find the following: Sarah was married on the 23 of November and gone to herself or her man. In another letter it indicates she was having a little trouble with Sarah before she married. I guess she was just a teenager and thought as all teens do all that time, she knew more than her mother. The man she married, I have been told was a Frenchman named Henry Harrip or Harop or as you have it Harrop. I am told when they were first married they lived in a dugout house in the north east part of Parowan. I remember my mother telling me she had a nice family of several children and they went through here with their family one time going to the St George Temple when they had their endowment and were sealed and had their family sealed to them.

Moving to Arizona

Teddy Parker, great grandson of Sarah writes: The family traveled with a group of people going to Arizona and were in Apache County, Arizona census records of 1880. The census lists Sarah as Indian female and all the kids as 1/2 Indian, Phoebe was 5. Lee’s ferry was operating during this time and that must have been the way they went. Possibly through Coyote (Antimony) Utah, at least in that general direction. Sarah no doubt had a hard time on the trip being with child. Henry must have helped her a great deal, but even riding in those wagons would have been hard.

Shortly after arriving in Arizona, Sarah died, along with twin boys, as a result of complications suffered during childbirth. The night Sarah died, Phoebe Lorraine, remembers being under the wagon wrapped in a quilt hearing her mother as she gave birth, she and the baby (Babies) both died and were buried in Snowflake, Arizona. As near as we can determine this was about 1881. Phoebe remembered her father making a casket for her Mother when she died and putting the little baby beside her. I’m sure it was hard for him to do this. He put the casket on two kitchen chairs. Then each of the children climbed up the rungs of the chairs to have a last look at their Mother.

After their Mother died the children were all farmed out to good Mormon families to live with and work for them while Henry went on down to the Mesa, area in Arizona to get a place for them, possibly to homestead. (They had to be good people to take one not their own to raise for a time.) Phoebe was 6 years old when Henry left her with a family in Snowflake, we do not know the name of the family. (Teddy Parker says that she probably told them but he does not remember the name.) She stood on boxes to wash the dishes. She remembered the area with great fondness and often told her grandchildren of things that went on there.

Daughter Phoebe Lorraine Harrop Black

Sarah, or Sara as it says on her headstone, was buried in the Snowflake, Arizona cemetery. Following are photos of her headstone, along with side headstones for the two twin boys who died with her.

Pahute (Paiute) Indian Law

Notes:

Based on research and in discussions with descendants of the Richard Benson family descendants, it is evident that Sarah was a native of the Pahute (Paiute) tribe. The Paiute Indians were the only Indians in the area surrounding Parowan. There was, and still is, an Indian tribe North and East of Parowan whose Chief was Wah-kar-ar “Walker.” When Walker, Chief of the Ute Indian Tribe, took children and traded them into slavery, it was usually to the Navajoes, who were glad to take them in exchange for blankets, beads and silver ornaments. Also, Chief Walker was a brother of Chief Cal-o-e-chipe, Chief of the Paiute tribe and would be less likely to take children from his brother’s tribe. Evidence points to the Paiutes selling their own children because they count not support them and preferred to have them live with the white people, as opposed to facing an unknown future.

The Ute Nation was presided over by a royal family, and so far as can be ascertained, the ruling heads of the five independent tribes were of the same royal stock. This at least was true as to the Pahutes (Paiutes). In the early settlement of Utah, Wah-kar-ar was the Chief of the Ute Nation. He is known in history as Walker, leader and instigator of The Walker War – an astute and resourceful Indian general whose military strategy would do honor to a West Point man.

The domain of the Pahute tribe was that country west of the range of mountains commonly called Wasatch, from Pahvant Valley in Millard County south to the Virgin River. Also that wedge of territory between the Virgin and Colorado Rivers front the Kaibab Mountains west to the junction of the two streams.

The great Pahute Chief Cal-o-e-chipe was a brother of Wah-kar-ar and had his headquarters on Coal Creek where Cedar City now stands. A lineal descendant of Cal-o-e-chipe is chief over the Cedar Indians to this day.

No direct system of taxation was levied by the Ute Nation upon the Pahute tribe but certain tributes of blankets or buckskins were demanded as occasion or whim of War-ka-ar determined. The fighting men of the tribe (called Ne-ro-quich) were also subject to draft.

The Southern Indians were always poor and were seldom able to pay the blanket tribute. In lieu thereof, Wah-kar-ar took children and these he traded into slavery, usually to the Navajoes who were glad to take them in exchange for blankets, beads and silver ornaments. This system of slavery was more or less common when the Mormons entered the country, and the breaking up by them of this pernicious evil somewhat compensates the natives for the overthrow of their government.

Paiute Indians in Parowan, Utah

The Pah Ute Indians are scattered along from Parowan southward to the Colorado. By the mid-1850s the Paiutes were experiencing a severe food shortage; they sold their children to the Mormons rather than watch them starve. During his first visit to what would become Parowan, Brigham Young said that he advised them to buy up the Lamanite (Indian) children as fast as they could, educate them and teach them the gospel, so that many generations would nor pass ere they should become a white and delightsome people …. I knew the Indians would dwindle away, but let a remnant of the seed of Joseph be saved. If they sold to the local Mormons, at least the Paiute parents would know where their children were.

Beneath These Red Cliffs, Ronald L. Holt

Sarah’s Legacy

We will never know where Sarah came from, or why she was sold to the Benson’s. What we do know is, although she had a relative short life, she left a wonderful posterity. We, her descendants, are very grateful to the Benson’s for taking care of her and raising her in an environment which prepared her to raise seven children through their early years .

Note:

Roberta B. Rowley, in a 1965 letter to Margret Hunter, talks about compiling a history of the Benson family from journals and first hand information in which she writes: “In the book where Richard Benson kept all these dates he also had the date of September 15th 1853 when he bought a little Indian girl for a blanket which the Indian mother was very glad to get. When sister Benson was ask what she did first when she found the little Indian child was now her own, she said she went in and gave it a good bath, put on clean clothes and burned the rags it had on. The family was always very kind to this Indian girl named Sarah. She was taught to mend her clothing and help with the housework. Sister Benson said she could bake bread to perfection. Sarah would watch the bread every minute of the time it was baking, but she was never allowed to mix it (because of her brown hands.) Sarah grew up in the family as one of them and the children were taught to treat her same as they did the other members of the family.”I have heard the oldest boy Richard Heber say his mother always seen to it that he danced with Sarah as well as his other sisters. I have heard my mother say that the Indian girl was not the child of the Indian woman who sold her but was a child that had been stolen from another tribe. The Bensons were always friendly to the Indians who come to their home asking for food. My mother said that Grandma Benson told her that she had a brightly pieced quilt on a bed when this Indian woman came in and it caught her eye so she begged grandma to give to her in exchange for the baby. I have no way of knowing the age of the child but I have been told she was only about two year of age as much as they could tell. From a letter written to Richard Benson, when he was on his second mission to England, by his wife Phebe. This letter is post marked December 24, 1866 I find the following: “Sarah was married on the 23 of November and gone to herself or her man. In another letter it indicates she was having a little trouble with Sarah before she married. I guess she was just a teenager and thought as all teens do all that time, she knew more than her mother. The man she married, I have been told was a Frenchman named Henry Harrip or Harop or as you have it Harrop. I am told when they were first married they lived in a dugout house in the north east part of Parowan. I remember my mother telling me she had a nice family of several children and they went through here with their family one time going to the St George Temple when they had their endowment and were sealed and had their family sealed to them.”

/-112.828,37.8422,12/300x200@2x.png?access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoiamJlcmdlbiIsImEiOiJjanRxb3d1NWgwaHBuM3lvMzJ3emtyNWY4In0.xCCZGVjZrBAKn5C_O6q8CA)

/-110.2665,34.4181,12/300x200@2x.png?access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoiamJlcmdlbiIsImEiOiJjanRxb3d1NWgwaHBuM3lvMzJ3emtyNWY4In0.xCCZGVjZrBAKn5C_O6q8CA)